Anyone who has their own children, or who has ever looked after children, knows that they often say and do things that adults would rather they didn’t.

They’ll tell your embarrassing secrets to a colleague without batting an eye, or they’ll ask inappropriate questions right at the moment you need them to keep quiet. Children often don’t filter what they’re thinking, especially if, to their knowledge, what they’re thinking and asking is completely socially acceptable to say aloud. As they get older, they start to learn what is and what isn’t appropriate to talk about publicly.

When children come across disability in a way they’ve never seen before, they’ll often ask very blunt questions. Things like, “Why can’t that lady walk?” or “Why does that man look like that?” As a parent or guardian, these types of questions can be confronting and difficult for us to answer.

They can also be really tough for the disabled person to overhear.

But it’s not your child’s fault They’re asking because we live in a society that largely excludes and hides disability. Often, they haven’t been exposed to it enough to understand what it is.

Although disabled people make up 25% of the population, they are only represented in the media 3.1% of the time. So, unless you were very intentional about it, it’s likely that your children haven’t seen disability represented in their world. Additionally, the unemployment rate is double for disabled people, which decreases the chances a child will have disabled teachers, librarians, doctors, or nannies.

We’re going to discuss how to approach disability with your children, and give you the tools that your parents probably wished they had when they were raising you!

Respecting privacy

Firstly, while it isn’t your child’s fault, this is a fantastic learning opportunity for them, and a great teaching opportunity for you. This is a moment where we can talk about how important it is to respect other people’s privacy and that there are certain questions that are inappropriate to ask – such as medical questions. You can also teach them that pointing and staring, whether a person is disabled or not, is unkind behavior.

Additionally, if you know the disabled person overheard, it would be polite to apologize. If they offer to talk to your child about it, and seem comfortable – then that’s great! But that needs to come from them personally.

Conversations at home

If something inappropriate does happen in public, this is a good moment to create an open channel of communication between you and your child to explain that if they do have questions, that’s okay, but they need to talk to you privately about them.

When you’re home – here are a few child-friendly things you can talk to them about:

- Everybody has a different kind of body – but no body is a bad body. All bodies are good bodies.

- When someone has a disability, it means that their body works differently, and sometimes looks different to what they’re used to seeing.

- Explain that disability is normal, that lots of people are disabled and it’s not a bad thing.

Preventative education

However, the best thing you can do as a parent or guardian is preventative education. If children understand disability and are exposed to disability from a young age, then they are far less likely to be confused by it, or ask questions that catch you off-guard.

You can educate them early by talking to them about disability and what being disabled means, and one of the easiest ways to do this is through books and television.

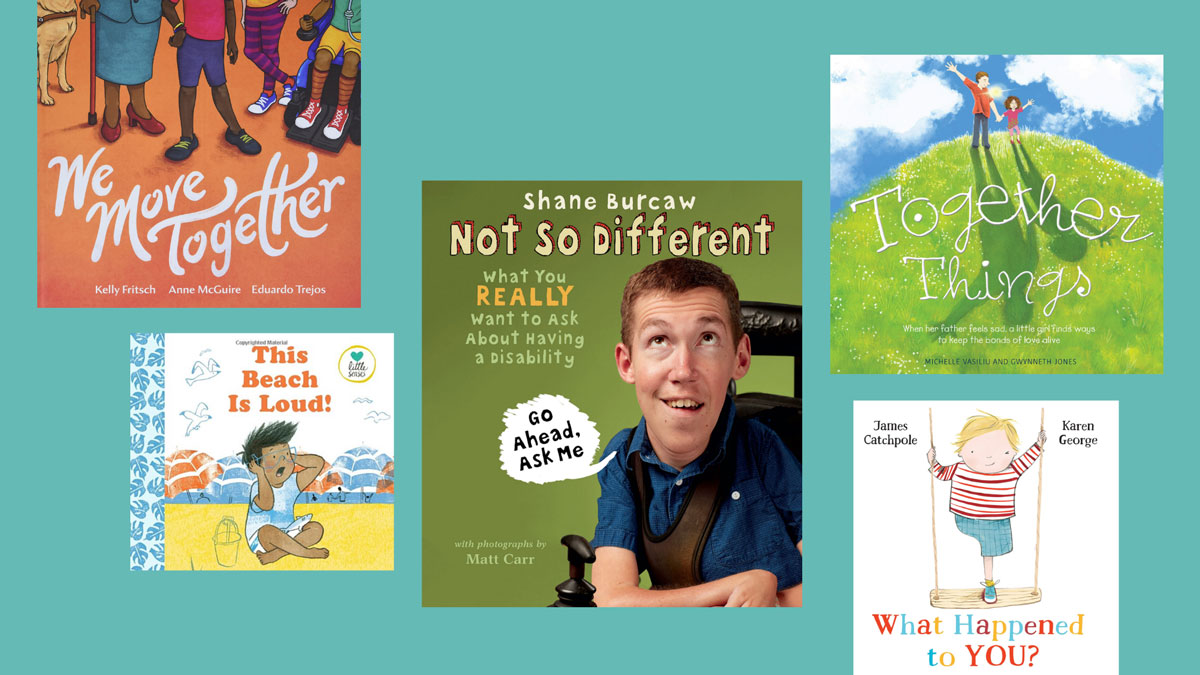

Here are 5 children’s books about disability, including neurodiversity and mental health conditions, that we recommend:

- “What Happened to You?” by James Catchpole

- “This Beach is Loud” by Samantha Cotterill

- “Not So Different” by Shane Burcaw

- “We Move Together” by Kelly Frisch

- “Together Things” by Michelle Vasiliu and Gwynneth Jones

Here are 3 shows we recommend that feature disabled characters:

- Llama Llama – features a character with a limb difference

- Paw Patrol – features a character that uses mobility aids, like a walker

- Sesame Street – features an autistic character

You can also talk to your child’s teachers, and find out if disability is being talked about in school. It’s important for them to be exposed to disability outside of your home environment as well.

The younger you start the conversation, the better – but it’s never too late! Even as adults, we’re all still learning and growing and teaching our children actually gives us the opportunity to rethink our own patterns of thinking.